The Moonless, the Midnight Eye, and the Season of the Last Gate

A day in a strange city with its own rules and rituals, including the ritual that marks Magda’s passage toward adulthood, all as described by her friend who won’t have his own Kite Day for a year or more.

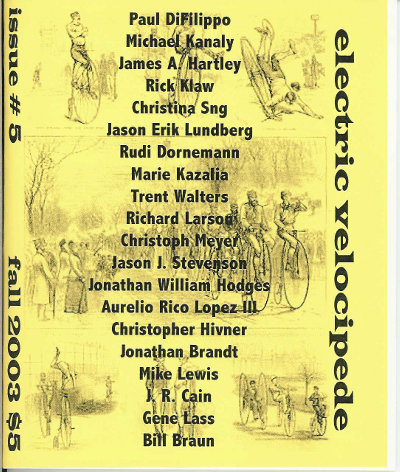

Way back in 1995, this story appeared in Shadowdance, a magazine that isn’t around any longer, and was later reprinted in issue 5 of the print magazine Electric Velocipede. It’s set in the same world– same city, even– as the later stories “Sunfast” and “Starblind.”

After “Starblind” was published, I mentioned the other two stories. Since “Moonless” isn’t online anywhere, I figured I’d put it here for anyone who’d like read the whole set and see where it all started.

The Moonless, the Midnight Eye, and the Season of the Last Gate

We’d come back around to the month for howling kites. At morning, we would lift them onto the wind and let them chew the bellies of clouds. We’d hear them all day, singing response and refrain to the huzz of the static mills. At evening, we would draw them down sodden and clotted.

In a cellar dug under the crossroads, we fed the steam. The oracle was freshly stoked and already babbling. Something about the twisted stair behind the sun. Something about generators, lenses and the echo of gears. On and on about the midnight eye.

Then this, muttered as the flame subsided: “revenants bound are alas forced so sleep against the far corner for the eye finds corners where there are none when everything else is spent and tell her to face the west at dawn.”

That’s what we’d been waiting to hear.

I waved a handful of glitter pennants and moved down the ritual stairs. I stored the pennants away in their cabinet and climbed the secular ladder. I walked home past the chains.

Under dusk, the city was a persistent itch. The watchers were boiling their suppers by now, up in their tower-top rooms. Down the alley, Osier, in a graffiti trance, was speaking in tongues all over the sidewalk and as high up the wall as he could reach. Around by the corner, kids were selling last night’s dreams for ice cream change. I’d trade a midnight eye to give away half as much.

The prism struck the hour of dogs.

A dance of rain and wires; wet concrete smudged with foxfire; a clutch of birds rattling from tree to tree to tree around the square. Moths with a pattern like hands on their wings clapped into the air. Who’s wearing the town mask this week? Drawing a bone whisk behind her as if sweeping the sand of the street, Magda was so light, she barely left any footprints to erase. I followed her back.

We ate in the hall, and after, she worked. She wound every thistle-barbed thread through the lace of her kite-day dress. I helped her keep the little lines from tangling, making a fence of angles with my hands. Her younger brother wrapped the knot where all the threads converged into the main line. We were done by the time the hour of the root struck and I went out to sleep.

I did not dig too deeply into the night; I woke easily and ahead of the dawn.

The prism struck the hour of the single raven. We gathered at the common.

Magda stood upwind of her own hands. Timing was the trick: to give the barb-ends to the wind just when a gust would set them well and solid in her skin. She caught the moment. We chanted and cheered and the kite rose from our hands. It did not tangle on the gargoyles of the fountain. It did not snag on awnings or catch on gutters.

Magda braced her feet and leaned back, and we heard wind in the throat of the kite.

We banked the public bonfires. We each began our day. The furrier loaned me the price of coffee. The mayor and the widow bantered mutual seduction. The plague doctor winced through his calisthenics. Newscriers claimed their corners. The fruit wagon was uncanvased. Osier scowled at last night’s inspiration. An applause of moths against the sky.

The kite keened and sighed to the push and ebb of the wind. Some strands of Magda’s hair came free of her braid to web themselves in among the lines standing out from her. A fingerlength of red in each line already. Good omen if a flyer stands long enough for the blood to rise up the line all the way to the kite itself.

The prism struck the hour of hands.

I spent the morning on the upper pier, loading, unloading crates of cages. I paired and portioned out silverfish. I fed the dragonflies sugar. I held my nose against the mantis breath. I cleaned the cages and revived the dead ones. I was only alone. It was done when I’d finished.

It was early and I sat and listened, and I could hear the drumming of jointed legs, the flickflick of caged wings, the sandy wind washing on the boards, the creak of my own spine, and the cicadas glistening out a harmony to the sound of Magda’s kite. I don’t know if there was a door slamming to tell me it was time or a shout from below, but I knew and I went down.

In the main room, we rolled a handful of dice, calculated, then found the page. A hymn of forgetting. We all hummed along, each in our key. After lunch I napped awhile in the candlefield.

Where the river bends, the tracks bend too, and the locomotive brakes spark on the turn. Every autumn the brush dries, and burns daily from the siding to the water. Ash snows on the churchyard. That day, it was a little after second noon. I went to tell Magda what she was missing, but her face was set in a trance distance. I stood there, as unspontaneous as ant’s hope, the prism beyond us turning shadows across the wheel. The kite cawing, cooing, calling, crowing. And I walked away while she bled at the sky.

From the hour of the chase through the hour of the triple queen, I tended the shadow garden. I directed the visitors. I explained the hard to see parts. I kept the children on the paths and out of the mirrors. Between these shepherdings, I pruned and tucked the wild edges, mulched the echoweed and forged a few entries in the guestbook. The hour of the kingdom seemed forever in coming.

Later, I changed. Osier found me and we talked of the day, of Magda, the kite, the morning’s crowd on the common, and the evening’s. He had been trying to understand what he’d written the night before. I’d been there, I’d watched while the muse rode him and I’d felt the frenzy like a storm charge in the air, but I couldn’t help him. I had iced and reasoned; I was not the same.

Near the river’s elbow, I hid a key in the clay and left my footprints in the fresh soot. Somewhere, the hour of hills was chiming. I hadn’t known it was so late, and had to hurry back.

It was cooler and nighthawks dodged ghosts in the churchyard. Moths in the candlefield flared and crisped, salting the ground with their seed. Tight between Magda and the kite, the line thrummed like a vein while the sky sipped her.

In the oracle’s fog, I have seen, as if sandwiched in a narrow wall of glass, fifty-two cross-sections of my own body. The map lace of arteries; the muddy stone of my brain; the jungle of my lungs; the crumpled glove of my heart; the net of lies and harm that is my nerves. I have seen them unknotted from each other and laid out smooth as roads. I understand that I am unseasoned and would make a poor sacrifice. If I tangle deeper into myself, if I climb higher in complexity, maybe a year or two and I can build my own kite.

Now, though, we carry Magda’s kite above her as she walks. We hold the line over our own heads (bloody all the way) and dance a cobra home.

We’ll bathe her in broth. We’ll wrap her in linen. We’ll her calm her with mirrors and sighs. She has the vigil still to sit through, the waiting with the chains on the steps, all that hollow time and the hope of the midnight eye. But I’ll be away and dreaming wide by then, and she’ll have a new name when I wake.

Rich as a moonless night all over her, those constellations of scars will be.